(Fiona Clark, email correspondence with Bridie Lonie 4/6/00)

In 1977 Fiona Clark was hit on the side of her face by a motorbike helmet as her car and the bike collided. The impact of the unbuckled helmet threw her right eye across her face and shattered bones in her face and jaw. She suffered the major impact of the accident.

Clark returned to photography as soon as she could see again, and continued the projects she had begun at Elam School of Art: exploring the life of her community in Taranaki and the gay community she had photographed as a student. She became interested in the processes of bodybuilding and its carnivals, following Mr New Zealand contests.

She documented the developing protests over her community at Waitara in the Think Big days of heady exploitation of natural resources. She engaged with the ecological battles over sewage disposal that were fought by Te Ati Awa, and followed these processes through their spiritual bases at Parihaka. She went to Europe and recorded the prehistoric sites of Southern England. Her saturated Cibachromes mirrored individual lives, idiosyncratic folk art constructions and the landscapes of Taranaki, a region which has always held its own position in the hierarchies of New Zealand identity. She recorded the mauves and pinks of the lesbian club in New Plymouth as it closed down. She taught and continued to maintain a rich working profile.

Quietly throughout the past 22 years she has also been documenting the processes of the gradual reconstruction of her face and the attendant histories of epilepsy, intermittent blindness and different degrees of pain. Her work has always emphasised sensory detail, eliciting from the domestic and the mundane singing harmonies and dissonances of colour. She insisted on the significance of the given, the image as recorded at the point of shutter closure, refusing to crop images or alter tonal balance. She maintained as far as possible a singular relationship between the act of taking the image and its record.

At the same time, in her home and its adjacent ex dairy-factory with its darkroom in the milk-rooms, collections of Taranaki’s material culture accumulated. Knitting patterns, dress-makers dummies, scarves, embroidery, doilies, tea-towels with inscriptions and patterns, buttons, button-hooks, plastic tablecloths, Images of women dressed up to receive their new washing machines or Kelvinators. The trappings of a dated but still expressive gender were folded and maintained in an archive somewhere between museum and work-box. This collection was compiled by Clark and by her then partner, Tertius. In its consistency and in the way in which it seemed to grow naturally from the Taranaki environment this collection demonstrated a more than nostalgic interest. An archaeology of a particular take on gender was being constructed.

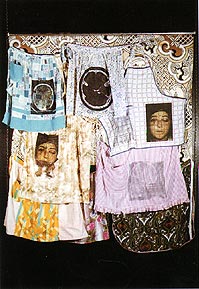

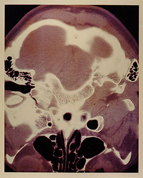

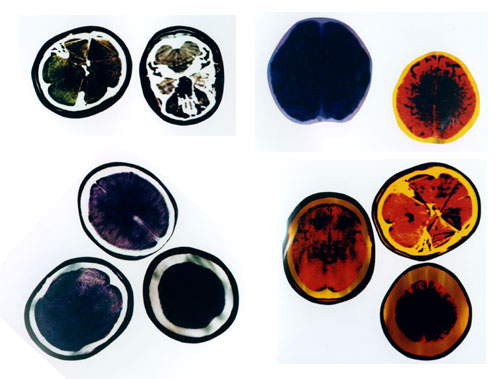

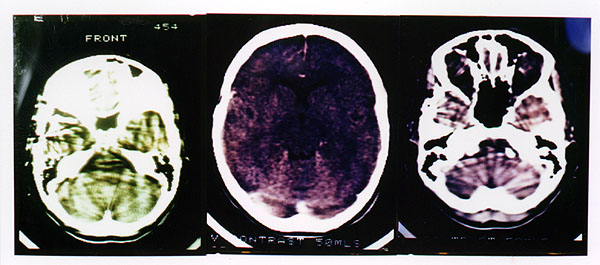

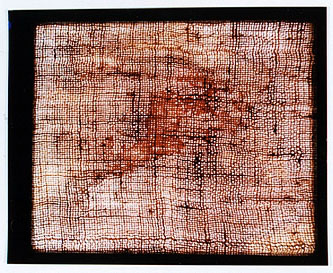

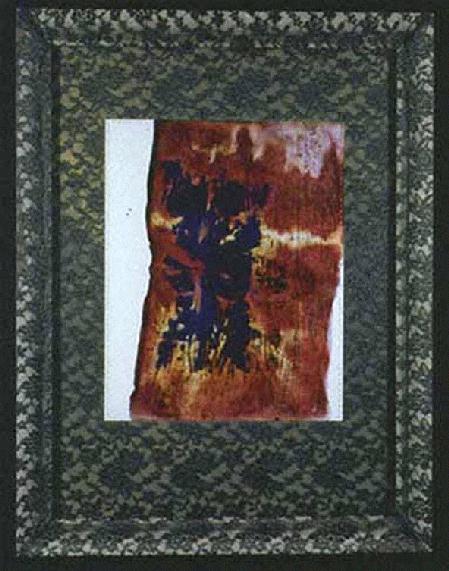

In 1997 Clark received a Creative New Zealand grant to work on the project she has called The Other Half. The results are documented in two very full folders of small photographic prints which record the work in its variety of forms. She has categorised the project into seven areas. These are The unconscious, conscious; Sight; The Brain, My Brain; Epilepsy and its effects, The sweet tormented brain; Teeth, Jaw, Mouth and Lips; Function, and Importance of Language. Media include photographs of different sorts, stitched cloths stained and dyed with fluids, bookworks, collages, woollen toys, oil and acrylic paintings, and most importantly the integration of body fluids into the work in tabulated methods, producing what she has called Genomegrams. She has copyrighted the products of this process under this name, and has a patent pending for the process. In this process, genetic material carried in histological specimens archived from the continuing medical interventions she experiences is integrated in a surprising number of ways into the photographic process. As well, the works include a rich mixture of photographic and textile practices, including computer-assisted embroidery. They range from the very small to the mural print and full-size patchwork quilt.

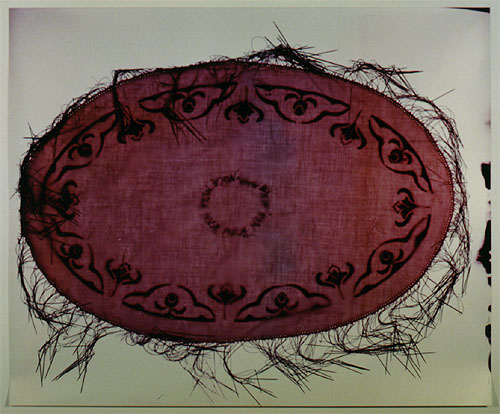

Reading the project as it is presented in the books, the first images record sensation that is gradually defined by language. Embroidery, lace and needlework present drawings from children’s letters, with shapes which seem filled with blood. Stitching and drawing become interchangeable, though stitching may also appear in the shared forms of pattern and border, precise and obedient, reproducing the imagery one finds on tray-cloths and in embroidery pages from women’s magazines of the forties and fifties. As this defined and collective imagery begins to appear so does language, which slowly articulates situations.

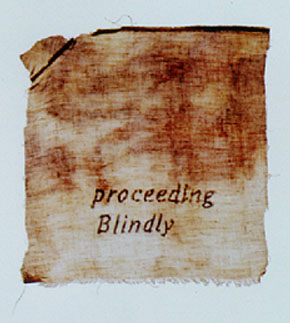

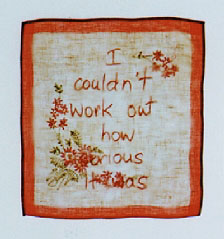

‘I cannot remember much of what happened’ occurs through several images of embroidered cloths, rags and cut clothing. “I couldn’t work out how serious it was” is recorded on an embroidered handkerchief, its large awkward daisies obscuring the last three words. This image is then recorded in negative and positive form through the process of retrospective staining and processing with body fluids resulting from the ongoing medical interventions Clark calls ‘tattooing’ in relation to her body.

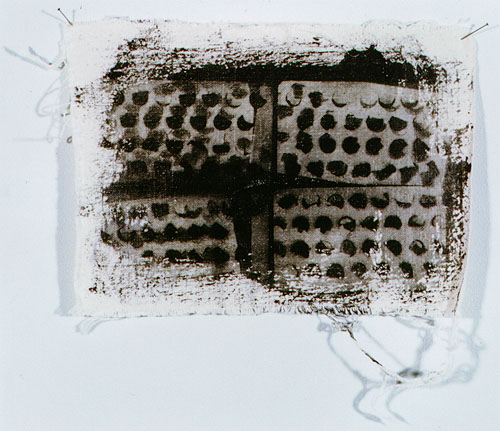

Clark worked on the series at different times during the project, and the development of technical processes and of imagery interweaves the project as a whole. Body fluids are used in different ways within all parts of the photographing, developing and printing processes. Positive colour printsand fibre-based black and white prints, consistently though not exclusively inter-relate stitching and staining, construction and spillages and leakages. Lace, embroidery, crochet, machine embroidery, embroidered texts on handkerchiefs, dish-towels, are embroidered or marked with half-sentences, repeated statements or injunctions. Doilies and brain-scans are printed together, one bleeding through the other. Images of quilts, notes, patterns for knickers, and a pattern for an eye patch integrate Clark’s cellular tissue, histological specimens containing her genetic material.

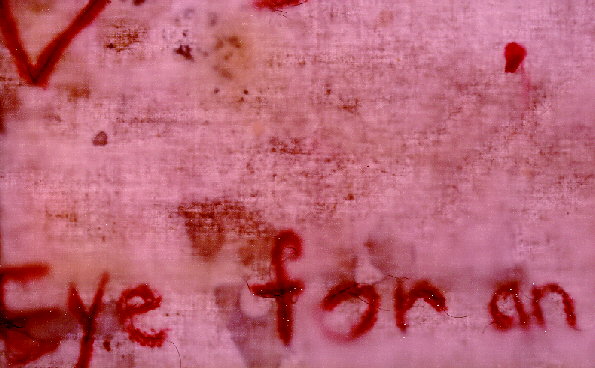

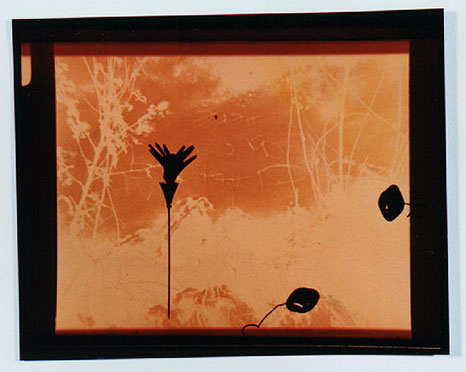

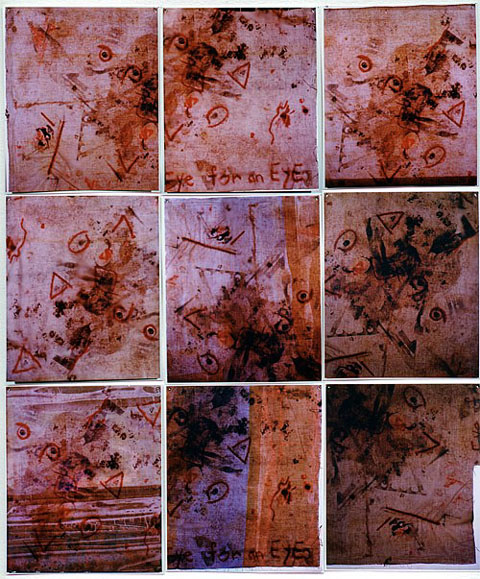

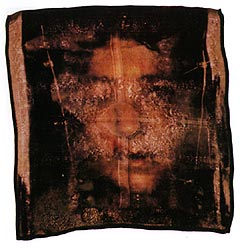

Internal/external processes of recognition are explored. Book Two of the record of this project begins with Nine genomegrams from “An Eye for an Eye” Cloth. Odd but clearly eye-shaped forms float haphazardly around stained and stitched fabric. The stitching becomes intensely specific, the words name and mimic savagely the stitched flesh and the floating elements of the face. Further images record Clark’s face at stages during her operations, as she and the diverse technical devices that pin, stitch, dis- and re-integrate the head are recorded as lists and as they function in the process. Within this series a 1999 group of images explores conscious and unconscious states with swirls of magenta and orange on cloth, and odd angular clarities of indeterminate objects written texts moving in and out of focus. The model is visual, the images seem to require a two-dimensional form, a flatness. Perhaps, after thirty years of work, a photographer’s sense of the unconscious has a particular form. However, these images also record the dissonance between the first understood image of herself and the requirement to relate to new self-image that was offered to her by the various mirrors of glass and the gaze of others as she proceeded with her life.

The socio-economic aspects of a functioning self which operates differently are documented in a book, “The Way I Walk”, which explores the effects upon the self in the workplace of strategies for handling, for instance, 30-second onsets of epilepsy, or days during which it is necessary to speak more slowly, to move oneself more consciously than at other times. Here Clark records the construction of an acceptable social self, and the effects of its occasional dissonances.

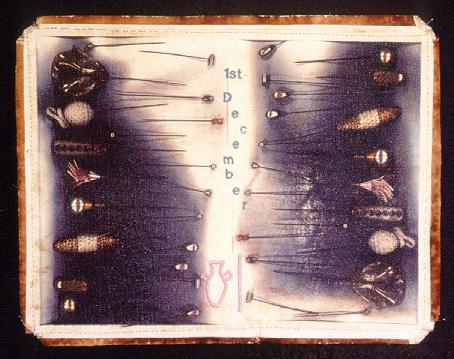

Another series, “Pink Swirl” documents her doctor’s laconic but necessary remark that if she were to be given a particular form of scan the metal plates in her head would reduce her brain as a fruit-milkshake is reduced to a homogeneous fluid. Like those which record the movement of her brain during the accident and the movement of her features during subsequent operations, these images disintegrate the parts of mind and consciousness, sight taste and touch. In these works the implications of thread and weave as integrative processes add horror to the wide, vacant stare of the eye floating without anchor, named in a separate piece in urgent chain-stitch. A set of brain-scan images, whole-head in profile, are overlaid with doilies and dress-maker’s pins, bandage and tied cloth, which is like the mutton-cloth used by butchers, integrates social identity with the raw exigencies of the living body, documenting the laws which hold them together.

These images have a relentless quality about them, in their archival approach and in their scrutiny of the possibilities of a record coming as close as it is possible for an image to be to the recorded person herself. The proximity of photographer and her genetic material through the mediums of the feminine stitch and all it speaks of claustrophobia, love and subversion, patchwork and “making do” is relayed to the viewer whose encounter with these works is made intimate through repetition and detail. We read the experiences through their impact upon the minutiae of daily experience, the hand-made and laboured elements of the embroidered tea-tray, the stains of illness upon them, or the woollen dolls whose floppy heads naturalised the experience of epilepsy for her.

Artists who use the processes of the archive as they construct works operate in a doubled time, in which each record signifies an end as well as a continuum. The miracle of genetic material is that it remains constant in a way that the body which yields it at discrete points in time does not appear to. There is a sort of loop of saved time, a continuity that argues with rotting cotton and thread or bloodied body. While this may be conceptual rather than actual , the genetic material in these fragments contains the possibility of resurrection in a more precise sense that does ordinary reproduction. At the same time, the death of each moment is recorded.

The intensity of the reconstruction of identity against the normal operations of youth, beauty and health is worked in with the operations of rural gender roles and the accomplishments of femininity. The work’s intimacy lies in the integrative nature of Clark’s processes as she works. Previously she has used her camera in a shared and negotiated process, working to present an agreed understanding of the image to the public. Here, she is both subject and recorder; but a strategic division operates throughout the process. The Other Half refers this work back to Fiona’s work as a whole, work which has as a major characteristic a clarity and transparency of purpose. The questioning that this body of work undertakes places that work in a different light as well, allowing one to see them dialogically, separating inside from out, always a problematic division but clearly strategic here.

The accumulated progress of this work implies that personality and identity are not definable but are aggregations. While the title suggests a detached observer, the work completes and integrates. There are social histories here, specific to Taranaki, and specific to medical histories of the late twentieth century. The processes bring imagery, relevant material products, affect and social environment into one compass. This archive is enormously rich. The work asks questions of its audience: how do we look on this face? How can we read this incoherent swirling pattern of memories and sensations? What is consciousness? What does pain mean to its observer? What relation does consciousness bear to the immediacies of pain, blackout and epilepsy? As a viewer, I feel fear, rage and celebration. I gain knowledge of an area that I might now imagine I understand; yet I would be very unwise to forget that this inferno is an artwork, a construction created with intelligence, discretion and clear sight.

Reproduced with Permission from:

ART NEW ZEALAND

Number 95, Winter 2000

P O Box 10249, Auckland 1003,

email: [email protected]